George Enescu (II): Manuscript of an orchestration by Enescu found by mistake

- Gabriel Bebeselea

- Aug 19, 2025

- 7 min read

Exactly 144 years ago, on August 19, 1881, George Enescu was born. And in the context of having discussed his Third Symphony in my previous blog post, here I would like to explore, from a very special perspective, his relationship with the one he called his “vice-mother,” Queen Elisabeth of Romania.

Four years ago, in June 2021, I found myself together with the historian of religions and Enescu scholar extraordinaire, Eugen Ciurtin, at the Library of the Romanian Academy. With the help of Mrs. Mădălina Lascu, bibliographer in the Manuscripts and Rare Books Cabinet of the Library of the Romanian Academy, I wished to see in person the sketches of the oratorio Strigoii (The Ghosts), set to a text by Mihai Eminescu, which Enescu had begun precisely when Bucharest was under siege during the World War I and continued at Iași and Tescani after the royal and governmental exile of 1916.

The sketches of the oratorio had been lost in the fog of war and were recovered only after Enescu’s death, in 1957, by the controversial Romeo Drăghici, founder of the George Enescu Museum (I recommend Eugen Ciurtin’s forensic writings on this subject). The fact remains that the sketches, even though they were complete and followed Eminescu’s text faithfully, had never been orchestrated.

Based on them, Cornel Țăranu created a version for voices and piano, which premiered in 1971, and after Sabin Păutza orchestrated it, I made the final corrections and recorded the oratorio Strigoii in 2017 together with the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin, Rodica Vică, Tiberius Simu, Bogdan Baciu, and Alin Anca – a co-production between Deutschlandfunk and the Capriccio record label:

The world premiere took place at Konzerthaus Berlin on September 26, 2019, with the same performers. I consider this oratorio extremely important and a true missing link in Enescu’s creation, because it is the first composition in which he experiments with compositional techniques (sprechgesang, microtones, polymodalism) and sonorities that he would later use and broaden in his magnum opus – Oedipe.

Although I had thoroughly studied the photocopies of the Strigoii sketches, which I had received from Cornel Țăranu while working together meticulously on the final corrections before the recordings, I had never managed to see the original manuscript.

So, upon arriving at the Manuscripts Cabinet, full of adrenaline at the thought of seeing a new Enescu manuscript, I discovered an intriguing and unexpected entry in the catalog. I requested that mystery manuscript, which I received after a few minutes (together with the complete sketches of Strigoii) and together with Eugen Ciurtin we stared at it in astonishment. It was not a composition, but an orchestration by George Enescu and its story is absolutely mind-blowing!

Approximately two weeks after the Battle of Verdun (with a colossal number of casualties, between 700,000 and 1,000,000), in the context of increasing pressure exerted on Romania by both the Central Powers and the Entente to join the World War I on one side or the other, Romania was to lose an important symbol of its moral compass: Queen Elisabeth (Carmen Sylva, under her literary pseudonym), who passed away on March 2, 1916.

With an exceptionally solid musical education, Elisabeth zu Wied had studied piano with none other than Clara Schumann. And if we have in mind that the first chapter of her memoirs is dedicated to Robert Schumann’s wife, we realize how influential and important music was to the woman who would later become Romania’s first queen.

The young George Enescu dedicated to her the composition that would propel him, at the age of 16, into the orbit of the most important composers after his immense success at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris on February 6, 1898 – the Romanian Poem Op. 1.

Shortly afterwards, Queen Elisabeth invited George Enescu to Bucharest with all the honors of royal protocol, where he was received by the High Council of Ministers and at the Royal Palace. On this occasion, Eduard Wachmann, founder of the Romanian Philharmonic Society (1868), organized a concert at the Romanian Athenaeum on March 1, 1898, in which Enescu performed as violin soloist. It was also here that the Romanian Poem was heard for the first time in Romania, having already become famous in the Parisian press. The most moving moment came when Wachmann handed the conducting baton to the young Enescu so that he could conduct the Romanian Poem himself – marking his conducting debut at almost 17 years old! The work was such a success that it was quickly rescheduled for March 8 and 15, 1898.

Soon, the queen had become a second mother to George Enescu, which is why he called her his “vice-mother.” Equally interesting is the nickname the queen gave Enescu, Pynx, derived from Sphinx, inspired by his taciturn nature. Very intriguingly, one of the most powerful, fascinating, and innovative moments in his opera Oedipe is the dialogue between the main character and the Sphinx (the death La Sphinge is strikingly emphasized by the terrifying glissando of a musical saw!).

From the moment of his debut in Bucharest on, George Enescu was frequently invited to the musical soirées organized by the queen, where Carmen Sylva herself would often accompany him on piano. Frequently, other musicians were also invited, and together with George Enescu and Queen Elisabeth they would perform famous pieces of chamber music. Among these musicians was the cellist and conductor Dimitrie Dinicu, from a renowned lăutar (traditional musician) dynasty, uncle of the famous violin virtuoso Grigoraș Dinicu (the composer of Hora staccato, made world-famous by Jascha Heifetz).

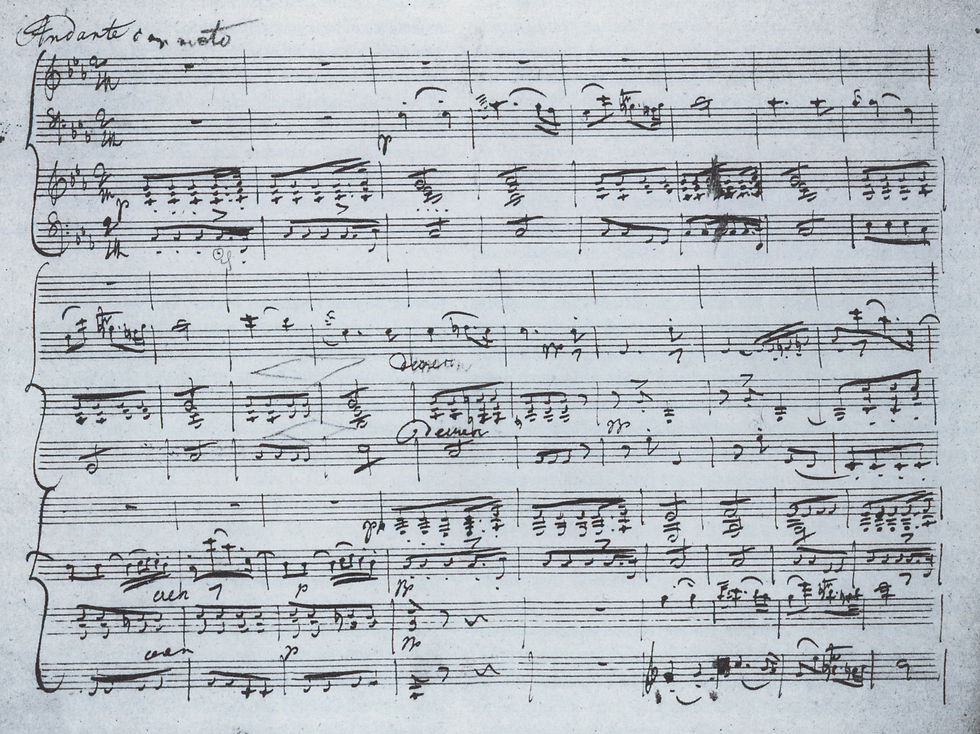

One of the queen’s favorite pieces was the Andante con moto from Franz Schubert’s Trio No. 2, Op. 100, a composition she often performed together with George Enescu and Dimitrie Dinicu. She was so fond of it that she requested it be performed by Enescu and Dinicu at her funeral. And it is no wonder, if we look at the journey of this composition.

This music, extremely intimate yet at the same time of exceptionally powerful impact, with clear references to the idea of a funeral march, was one of the last pieces Schubert heard performed. Composed just a few months before his sudden death at only 31 years of age, the Andante con moto has a profoundly premonitory character and an ostinato that recalls the funeral march written by Beethoven a quarter of a century earlier, in the midst of Napoleonic triumph and subsequent disillusionment.

At the foundation of this movement lies a Swedish folk song, Se solen sjunker (Watching the Sunset), which Schubert had heard performed by the Swedish tenor Isak Albert Berg:

This feeling of parting and disappearance shines through, as the text of this song is a metaphor for death, (a feeling heightened by the key of C minor used by Schubert in his Andante con moto):

See the sun is setting fast behind each mountain peak.

Every night comes with dark shadows, you flee, sweet hope now bleak.

Farewell. Farewell.

Ah, the friend’s thoughts are no more of his fair and faithful bride.

But when the queen died, Enescu – who had rushed from Paris as soon as he heard the news of his “vice-mother’s” severe pneumonia – was quarantined in a room at Metropole Hotel, across from the Royal Palace. He was suffering from mumps and was not allowed to leave that room, which prevented him from seeing the queen on her deathbed – extremely heartbreaking for Enescu.

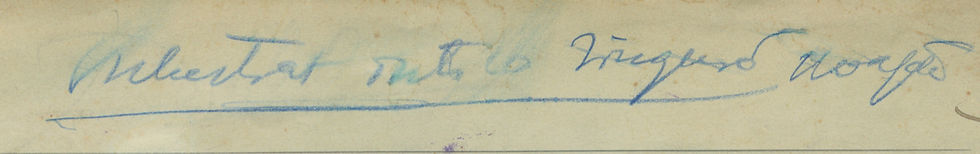

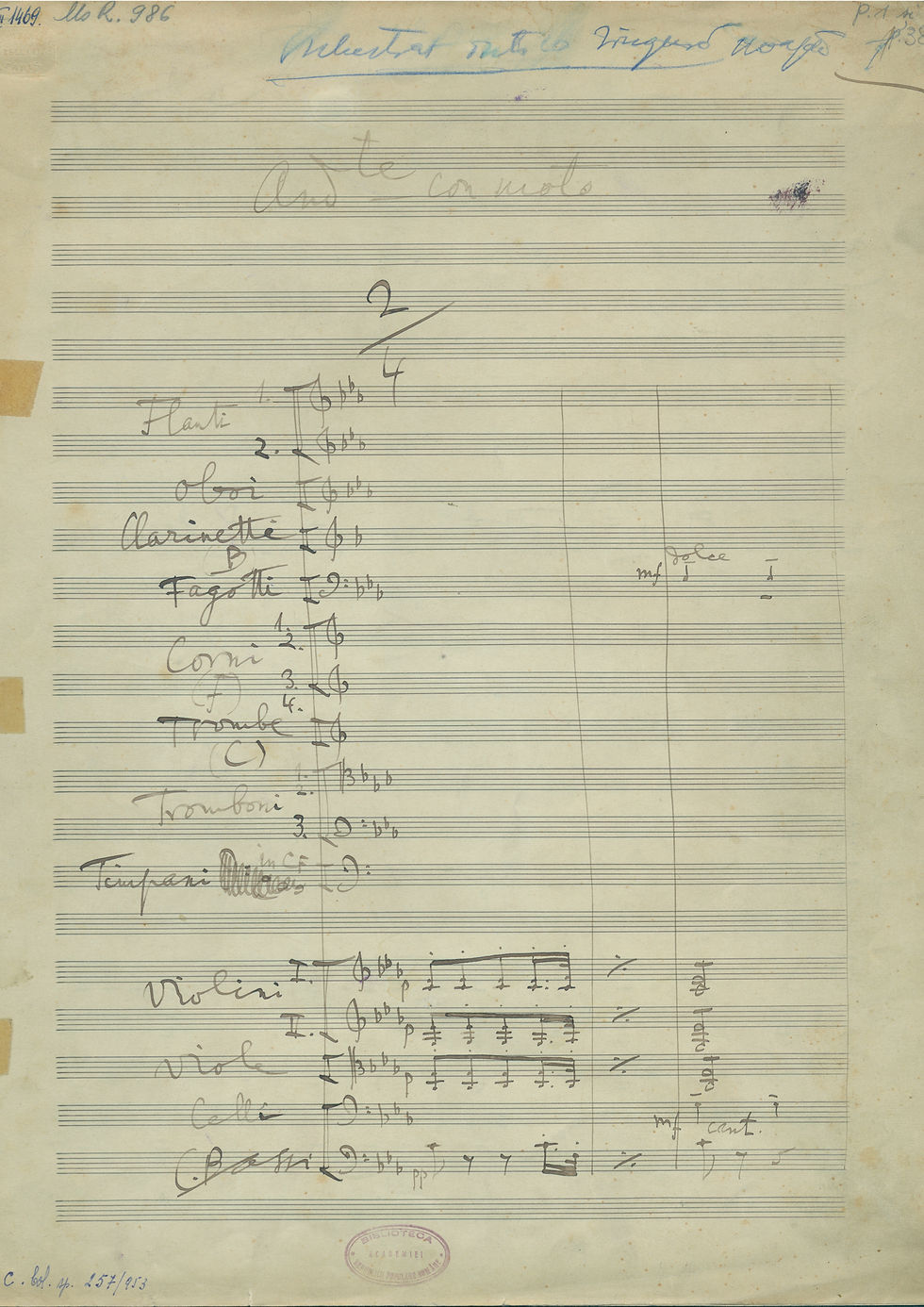

To honor the queen’s wish, Enescu started to orchestrate the Andante con moto, while Dimitrie Dinicu would conduct the Orchestra of Public Instruction, an ensemble under the queen’s high patronage. Orchestrated in a single night, as Enescu himself noted in blue pencil on the manuscript, the orchestral parts were prepared immediately as he completed each page, and by 10:00 a.m. next morning Dinicu was already rehearsing with the orchestra in order to perform the work that very evening.

Orchestrat într-o singură noapte (Orchestrated in a single night):

Even the most important newspapers in Bucharest, which covered exclusively the royal funeral, devoted significant space to George Enescu’s act of heroism and selflessness in orchestrating the work against the clock — and all this while burning with a high fever.

The second performance of this piece took place on March 19, 1916, at the Romanian Athenaeum, again with Dimitrie Dinicu at the podium, in a special concert in memory of the Queen. This concert also included Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 Eroica (the connection with the funeral march in the second movement being clear), Chopin’s Piano Concerto No. 2 (with Marie Gabriele Leschetizky), and Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3. The repertoire was closely tied to the pieces Queen Elisabeth herself played and to her personal preferences.

In the article “Memories about Carmen Sylva”, Enescu wrote: “Only a year or two later was I able to listen to this composition, first performed when I lay ill in bed, deeply saddened by the death of Carmen Sylva, the unfailing embodiment of kindness.” Yet Enescu himself conducted this orchestration at the Athenaeum less than two months after its premiere, on May 6, 1916, in a concert organized by the Society of the Friends of the Blind in Romania (founded by Queen Elisabeth in 1906 and presided over by Queen Marie).

After 1916, Enescu’s orchestration was completely ignored and forgotten for 105 years, until 2021, when I came across the work completely by mistake.

After I transcribed the manuscript, I was honored to conduct the modern premiere of this masterpiece, on March 10, 2022, once again at the Romanian Athenaeum, with the “George Enescu” Philharmonic, in a concert whose central figures were Queen Elisabeth of Romania, Clara Schumann, and Queen Victoria of Great Britain, each represented by a work in the program:

Franz Schubert / George Enescu – Andante con moto (modern premiere)

Robert Schumann – Violin Concerto with Sayaka Shoji (its second movement dedicated to Clara Schumann, with the theme that Schumann claimed, months later, had been dictated to him by the spirits of Mendelssohn and Schubert as material for what would become the Geistervariationen)

Felix Mendelssohn – Symphony No. 3 “Scottish” (dedicated to Queen Victoria of Great Britain)

For the Romanian readers, more on this topic can be found in my book Musica Ricercata sau 11 povestiri muzicale surprinzătoare, Humanitas, 2024

Comments